Classic Arms Review: M1 Carbine

As the grandson of a World War Two US Navy veteran, I’ve been fortunate to one of the first people my grandfather has shared his Pacific Theater experiences with and in our numerous discussions, he has frequently mentioned his love for his issued M1 Carbine.

Thanks to his glowing feedback for this classic American carbine, I purchased an Inland Manufacturing Rack Grade example from the CMP several years ago. Though I’ve owned my M1 for quite a while, only recently have I begun to shoot it with any sort of regularity. Since the carbine was a bit of an oddball for its time, it is deserving of closer examination.

Note: This review is intended to outline general M1 Carbine use and practicality. Readers looking for a detailed discussion of carbine evolutionary changes and parts breakdown should consider other, M1 Carbine-centric sources.

History and Development

As most firearms historians would tell you, the M1 Carbine has always been one of the misfits of the gun world. In some ways, the carbine was arguably the first personal defense weapon (PDW) and far ahead of its time. By other measures, it was little more than an early pistol caliber carbine that excelled in few meaningful ways aside from its impressively lightweight. Like many disputes, the truth probably falls somewhere in between these two extremes, but for its time, the M1 Carbine was just the rifle that rear line and specialty troops needed as WWII escalated into a truly global conflict.

While initial requests for a short, semi-automatic rifle were first submitted to the US Ordnance Department in 1938, the actual development of the M1 Carbine did not begin until 1940. By 1941, several companies and independent designers had completed working prototypes for trials, but as a whole, the submissions were disappointing and unfit for service. As a result, Ordnance rejected all initial samples for the new carbine.

Shortly after the trials, the famous Winchester Repeating Arms Company reached out to Ordnance regarding the .30-06 M2 rifle (commercially the G30) that had originally been conceived by Ed Browning and was later refined by David Marshall “Carbine” Williams. Though Ordnance did not want the M2, the prevailing belief was that the design could be reduced to carbine size and chambered in the new .30 Carbine for an extremely maneuverable rifle. After Ordnance demanded a short notice prototype, Winchester developers set out to build the envisioned firearm. Remarkably, the design group completed their prototype in less than two weeks.

The Winchester prototype was a resounding success, and Ordnance directed the company to come up with a more formal submission to compete against other designs in September 1941. At the September trials, Winchester’s carbine again prevailed over other submissions and was officially approved as the United States Carbine, Caliber .30, M1 on October 22, 1941. The first orders were not delivered until 1942.

The M1 Carbine served throughout WWII in both Europe and the Pacific. After WWII, it also served in the Korean War and Vietnam. In 1944, a select-fire version of the M1 Carbine was developed and dubbed the M2 Carbine. It saw limited action during 1945 in both theaters of the war, but most of the M2’s service came in Korea and Vietnam. In the late stages of WWII, a third variant, the T3 Carbine, was developed and issued to troops, primarily those fighting in the Pacific. The T3 carried the US Military’s first-night vision scope, the M2 “sniper scope.” Like the M2 Carbine, the T3 saw extremely limited use in WWII, but it proved effective during its stint on the frontlines.

Thanks to WWII manufacturing challenges, M1 Carbine production was assigned to nine separate companies, only one of which produced firearms regularly. These included (in descending order by production) Inland Manufacturing (General Motors), Winchester Repeating Arms, Underwood, Saginaw Steering Gear (General Motors), National Postal Meter, Quality Hardware & Machine, International Business Machines (IBM), Standard Products, and Rock-Ola. Inland produced the most rifles by far (approximately 43%), and despite leading the development of the carbine, Winchester was a distant second in terms of production (around 13% of total M1 Carbines made).

Design

The M1 Carbine is a gas-operated rifle that uses a short-stroke tappet system. Unlike long-stroke systems and other short-stroke designs, the tappet is captured within the rifle’s gas block and is not intended to be removed during normal servicing. As a short-stroke piston, the tappet only applies force to the operating rod/slide for a very short distance. Once the slide begins to move rearward and separates from the tappet, inertia carries the action through the rest of the cycling process.

Like the M1 Garand, the M1 Carbine uses a rotating bolt. This design was found to be superior to Ed Browning’s tilting bolt that was originally developed for the carbine’s predecessor. Because the bolt is similar to the Garand, many shooters incorrectly assume the M1 Carbine is a sized-down version of the famous battle rifle.

The carbine’s metal parts are mostly finished in a gray phosphate. However, most original and properly refinished guns should have blued bolts and magazines. For this reason, it is normal for an M1 Carbine to sport a bolt that does not match the rest of the rifle in color.

Disassembly of the M1 Carbine is simple. Just loosen the screw on the barrel band and depress the retaining spring. With the barrel band forward off the stock, the action and upper handguard will lift up and separate. Readers will notice that my carbine’s barrel band features a bayonet lug. Most WWII M1 Carbines had simple bands with no bayonet provisions, and the lugs were not added until the Type 3 bands were introduced late in the war.

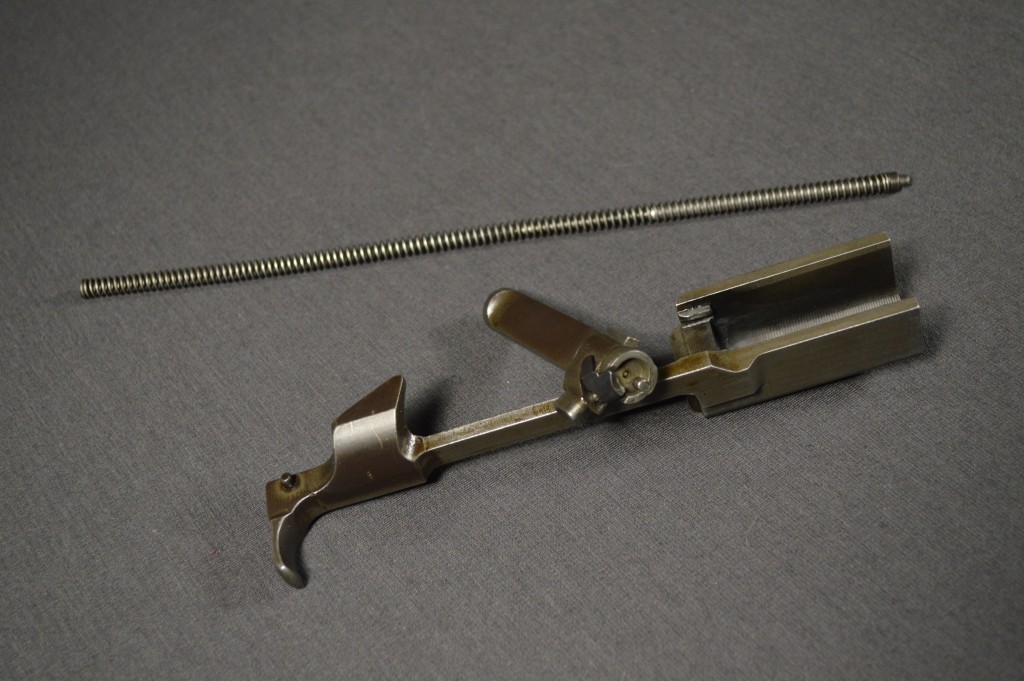

Removal of the bolt can be accomplished by pulling the slide to the rear and lifting it off its track on the right side of the receiver. With the bolt out, remove the recoil spring and guide. The slide can now be removed from the barreled action through a cut out in the barrel. Reassembly is conceptually straightforward and is essentially the reverse of this process, but getting the bolt back into its channel can take some practice. The trigger assembly is secured to the receiver with a simple cross pin forward of the magazine well.

Size and Weight

The M1 Carbine is a featherweight compared to most other military rifles of its era. At just a hair over five pounds, the carbine is only slightly over half the weight of the standard M1 Garand. Thanks to its short receiver and 18 inch barrel, the M1 Carbine has a total length of just 35.5 inches. Unlike most other WWII long guns, the carbine is truly a firearm that I could see carrying day in and day out. Even compared to modern rifles, it still ranks among the handiest options (subjectively speaking) available today.

Ammunition

The .30 Carbine round developed for use with the M1 was arguably the first intermediate rifle cartridge to be widely adopted by a major military. Unlike most cartridges of its era, all .30 Carbine ammunition used by US forces employed non-corrosive primers, and as a result, most surplus carbines still carry their original barrels. With a 110-grain FMJ bullet traveling at approximately 2,000 feet per second, the .30 Carbine offers over 950 ft-lbs at the muzzle. This is considerably more powerful than even the hottest .357 Magnum loads, but it does not quite match up to more modern intermediate cartridges. Given these numbers, it is safe to dismiss the old rumor that the .30 Carbine failed to penetrate Korean and Chinese winter gear during the Korean War. The effective range of the round is relatively limited at approximately 300 yards, and its velocity does begin to drop off significantly after around 200 yards. Of all the .30 caliber rifle rounds I’ve fired, the .30 Carbine is unsurprisingly the most pleasant.

Magazines

The M1 Carbine feeds from double stack 15 or 30 round steel magazines. The 15 round versions were far more common in WWII as the 30 round; curved magazines were not developed until the M2 hit in 1945. From my experience, the magazine is one of the weakest points of the M1 Carbine. The thin steel dents easily and the floorplate has a tendency to slip on some examples.

Sights

The vast majority of WWII M1 Carbines featured a simple dual aperture rear peep sight and shielded front post. The rear flip sight offered apertures calibrated for 150 and 300 yards. Later in the war, two versions (milled and stamped) of adjustable sights were introduced. The adjustable version allowed for increased granularity, with marked settings for 100 yards to 300 yards in 50-yard increments. The late rear sights also allowed soldiers to adjust windage in the field using a knob on the right side of the unit. My example features one of the Type 2 milled adjustable sights.

Trigger

The trigger is easily my least favorite part of the M1 Carbine. While it is always a bit difficult to draw comparisons between well used military surplus rifles, the carbine’s single-stage trigger pull hovers in the 6.5-pound ballpark according to my Lyman gauge. Reset is quite short at around 2mm, and there is no take-up to speak of. In all honesty, the M1 Carbine’s trigger is not terrible; it just does not compare well at all to the Garand’s two-stage bang switch.

Most WWII-era carbines came with a push-button safety that could be found just behind the magazine release. Late in the war and during arsenal refurbishment, many rifles were outfitted with rotary safeties with levers on the right side of the gun. Personally, I prefer the rotary design as it is much more obvious that the rifle is set to safe.

Range Report

The M1 Carbine is a rifle that I could truly shoot all day long. It offers more recoil than a .22 LR long gun, but far less than your average WWII rifle. If you’re looking to step a new shooter up to something a little more powerful than a Ruger 10/22, the M1 Carbine is the logical choice. Even considering its pleasant disposition, the M1’s .30 Carbine round is more than adequate for defensive purposes or hunting small-to-medium sized game.

I have found that my M1 Carbine is a finicky beast at the range. Sadly, my example has a disappointing tendency to improperly eject spent casings after firing, causing stovepipe failures. Though I have thoroughly cleaned the M1, most collectors attribute these hiccups to worn extractors or stiff/broken ejectors. I’ll have to spend more time with the rifle diagnosing these issues, but it is not all that surprising that a well-worn example like this would have a few problems. For reference, this was a Rack Grade M1 from the CMP.

Most sources I’ve seen rate the M1 Carbine as a three to five minute of arc (MOA) rifle. While it is far from a sub-MOA shooter, I feel that it is much more accurate than five MOA. Even my well-worn M1 (2+ muzzle erosion) is capable of stacking rounds at 25 yards, and hitting clay pigeons with it at 100 yards is relatively trivial. The M1 Carbine’s peep sights are excellent for range work, and as long as the barrel is in decent shape, groupings in the two to four MOA range should certainly be manageable.

Conclusion

The most disappointing aspect of the M1 Carbine is the fact that new imports/Lend-Lease returns have mostly dried up. As such, prices for these classic rifles have increased significantly over the last four or five years, and most good examples currently sell for $800 to $1,000. Even at those prices, my admittedly biased opinion is that the M1 Carbine is well worth serious consideration. Shooters will be hard-pressed to find a more enjoyable WWII carbine for range use, and collectors need at least one carbine to round out a WWII collection.

An information security professional by day and gun blogger by night, Nathan started his firearms journey at 16 years old as a collector of C&R rifles. These days, you’re likely to find him shooting something a bit more modern – and usually equipped with a suppressor – but his passion for firearms with military heritage has never waned. Over the last five years, Nathan has written about a variety of firearms topics, including Second Amendment politics and gun and gear reviews. When he isn’t shooting or writing, Nathan nerds out over computers, 3D printing, and Star Wars.